[Engaging Books is a monthly series featuring new and forthcoming books in Middle East Studies from publishers around the globe. Each installment highlights a trending topic in the MENA publishing world and includes excerpts from the selected volumes.This installment involves a selection from the American University in Cairo University Press on the theme of Cairo architecture. Other publishers’ books will follow on a monthly basis.]

Table of Contents

Cairo since 1900: An Architectural Guide

By Mohamed Elshahed

About the Book

About the Author

In the Media / Scholarly Praise

Additional Information

Where to Purchase

Excerpt

Call for Reviews

Hassan Fathy: An Architectural Life

Edited by Leila el-Wakil

About the Book

About the Author

In the Media

Additional Information

Where to Purchase

Excerpt

Call for Reviews

A Field Guide to the Street Names of Central Cairo

By Humphrey Davies and Lesley Lababidi

About the Book

About the Authors

In the Media

Additional Information

Where to Purchase

Excerpt

Call for Reviews

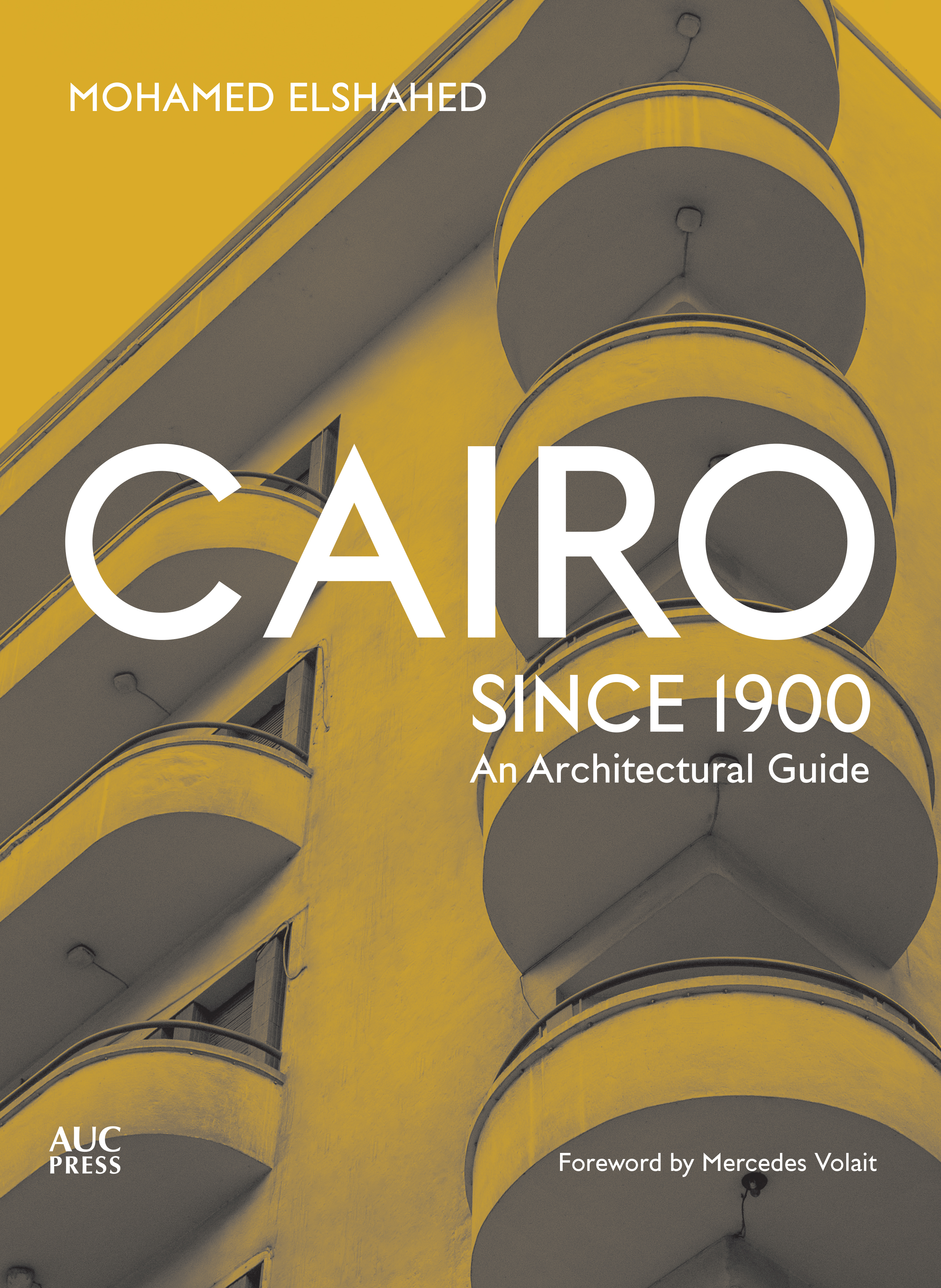

Cairo since 1900: An Architectural Guide

By Mohamed Elshahed

About the Book

The city of a thousand minarets is also the city of eclectic modern constructions, turn-of-the-century revivalism and romanticism, concrete expressionism, and modernist design. Yet while much has been published on Cairo’s ancient, medieval, and early-modern architectural heritage, the city’s modern architecture has to date not received the attention it deserves. Cairo since 1900: An Architectural Guide is the first comprehensive architectural guide to the constructions that have shaped and continue to shape the Egyptian capital since the early twentieth century.

From the sleek apartment tower for Inji Zada in Ghamra designed by Antoine Selim Nahas in 1937, to the city’s many examples of experimental church architecture, and visible landmarks such as the Mugamma and Arab League buildings, Cairo is home to a rich store of modernist building styles. Arranged by geographical area, the guide includes entries for more than 220 buildings and sites of note, each entry consisting of concise, explanatory text describing the building and its significance accompanied by photographs, drawings, and maps. This pocket-sized volume is an ideal companion for the city’s visitors and residents as well as an invaluable resource for scholars and students of Cairo’s architecture and urban history.

About the Author

Mohamed Elshahed is a researcher, curator, and specialist on architecture, design, and material culture in Egypt. He holds a PhD from New York University and an MA from MIT. He is the curator of the Modern Egypt Project at the British Museum and founder of Cairobserver.com.

In the Media / Scholarly Praise for Cairo Since 1900

“Extraordinary and unreservedly recommended”―Midwest Book Review

“Cairo’s modernism—as described by Elshahed—isn’t defined by any particular philosophy, whether local or foreign. Instead, its hallmark is an eclectic hybridity.”—Marcia Lynx Qualey, Qantara.de

“[T]he book is beautifully designed, as elegant and functional as many of the buildings it documents. It is a small, compact, softcover volume that can be carried along as one explores the city.—Ursula Lindsey, Al-Fanar Media

“Everything from bridges to gardens, from iconic buildings to unknown residential buildings with a story to be told.”―Shaimaa S. Ashour, Maydan

“Cairo since 1900 is a timely addition to our appreciation of Cairo’s urban fabric. With meticulous research and beautiful photographs, Elshahed offers us a unique survey of the city’s modernist architectural gems.”—Khaled Fahmy, University of Cambridge

“Architectural historian and publisher Mohamed Elshahed is safeguarding the architectural history of Cairo – and the rest of Egypt.”―Rima Alsammarae, Architectural Digest (Middle East)

“Cairo since 1900: An Architectural Guide not only fills an immense gap in the architectural history of the region, but also makes a much-needed intervention into the history of global modernism. The urban fabric of this cosmopolitan and vibrant city is described in rich detail, with information on the architects as well as the patrons who gave shape to it. It will serve as an essential guide to understanding, visiting, and studying modern Cairo.”—Kishwar Rizvi, Yale University

“The Egyptian capital, for too many visitors, is a bewildering urban fabric to be traversed in search of antiquity, circum-navigated to reach the pyramids of Giza, or bisected rapidly to reach historic mosques. Yet to the trained eye sprawling Cairo’s modern fabric spells out the fascinating history of twentieth-century Egypt. Scholarly and user-friendly at the same time, this indispensable guide is a veritable Rosetta stone for decoding the various languages in which the quest for modernization and identity was expressed in concrete, steel, brick, and stone.”—Barry Bergdoll, Columbia University

Additional Information

English edition

10 December 2019

410 pp.

$39.95

ISBN: 9789774168697

Where to Purchase

UK: Bloomsbury | Amazon UK

Excerpt

Introduction:

Cairo is essentially a twentieth-century city. Its expansion and development during the past century surpassed the pace and scope of its growth over the previous millennium. According to the census of Egypt, the population of Greater Cairo grew from two and a half million inhabitants in 1947 to more than twelve million in 2009. More people meant more buildings, though not necessarily more architecture. Between 1952 and 1965 over fifteen thousand public housing units were built in Cairo, barely absorbing the city’s growing population in need of affordable housing. Architects provided designs for some of Cairo’s residents with more visible impact in the 1920s to 1960s, with their work clustered in specific areas and mostly catering to the city’s bourgeoisie or state commissions. The majority of the population built without the services of trained architects.

Today, the legacy of the city’s homegrown architects who shaped its landscape is entirely absent from public knowledge. If asked, most Cairenes could not name a handful or even one of the city’s prolific architects from the past century. Despite this, architecture was big business in twentieth-century Cairo. Real-estate development boomed around the turn of the century until 1907, and again in the 1930s and 1950s. Mortgages and insurance policies were powerful engines for Cairo’s urban development during the first half of the century. Architectural production was extensive, and architects often took on the role of contractor. The profession was driven less by theory and more by real-estate demand. Modernist architectural features were ubiquitous. They were common in districts such as Dokki, Agouza, and Heliopolis, inhabited by the new classes that formed after the 1919 Revolution, who embraced the Modernist house or apartment as the materialization of new notions of class, identity, and modernity.

With modernization comes destruction. Although Cairo escaped damage during the Second World War, there has been significant loss of the city’s architectural heritage since then—particularly modern constructions, which are seen as possessing little cultural value—with many buildings erased without documentation or severely mutated. In many ways this is nothing new for Cairo. In 1945 architect Sayed Karim described Cairo’s slow incremental deterioration in times of peace as causing the city more damage than that experienced by European cities in the war. He added that catastrophic damage allowed European architects to innovate and to rebuild cities according to modern concepts and designs, something that was not afforded to Egyptian architects.

In January 1952 riots against British occupation in downtown Cairo damaged hundreds of properties. The so-called Cairo Fire, however, had little impact on the city’s architectural development. Arson targeted stores and shopping emporiums as well as banks and airline offices and most fires were contained. Furthermore, the fires were limited to the downtown area, leaving the rest of the city without damage. The Cairo Fire, in which Karim’s own office fell victim to the flames from the stores below, did not amount to the catastrophe that could have generated a new urban order.

Cairo is an unstable city; it constantly changes its skin, transforming its urban and architectural character in a piecemeal fashion and at a speed that far surpasses the pace of scholarship and documentation. The city tests the permanence of buildings, as structures built to last generations often have short shelf lives and are replaced or modified multiple times within the span of a century. Many of Cairo’s iconic buildings today replaced earlier structures.

The monumental Immobilia Building (1940, #31) replaced the Neo-Islamic palace Hotel Saint-Maurice (1879) that housed the French Consulate; the sprawling October Bridge (1969–99, #159) required the demolition of several buildings along its path such as the Anglican All Saints Cathedral (1938, see #137), a cornerstone of colonial Cairo. The Arab League Building (1955, #11) and the Nile Hilton (1958, #10) were built on land previously occupied by the army barracks built in 1856 that later housed British troops from 1882 until 1947 when it was demolished.

The massive Intercontinental Hotel replaced the old Semiramis Hotel (1907). Next door to the Egyptian Museum (1902, #8), the former headquarters of the National Democratic Party (1959, #9), originally erected to house Cairo’s municipality, was demolished in the early days of conceiving this book. Efforts to save the building from demolition, for its architectural or historic value, failed. The building’s Modernist design was equated in public discourse with ugliness, a necessary maneuver to facilitate its demolition. Numerous houses, apartment blocks, public buildings, and entire districts built in the span of the twentieth century across Cairo’s vast geography have been demolished in the past three decades to satisfy the insatiable real estate market currently producing buildings that lack any architectural point of view. Other demolitions make room for piecemeal development projects led by state institutions. Modern structures disappear without record; they casually ‘melt into air’ as if they had never existed.

Modernism in Egypt has not been granted national heritage status, as if history stopped at the threshold of the twentieth century. There are no specialist government or private bodies recognizing, archiving, documenting, or protecting Modernist buildings. In Egyptian universities architectural education marginalizes and often omits the history of modern architecture. While there are departments of architecture in nearly all major universities, enrolling hundreds of students every year, they graduate without taking a survey course on the history of modern architecture in Egypt, a major blind spot in architectural education. This situation has led not only to the loss of this important architectural heritage in the city but also the irreversible loss of entire archives of architects whose oeuvre was reduced to rubble after they passed away. The lack of recognition and documentation of Modernist design means that there are no professionals prepared with the tools to conserve a modern building.

Renovations of modern buildings are rare, and they often amount to redesign rather than refurbishment. For example, the Automobile Club in Downtown, built 1923, had a minimalist façade but it received a facelift in 2008 that resulted in the addition of Classical

European decorative features seen today as signs of status and prestige. Plaster Corinthian capitals, cornices, and columns are often added to embellish previously Modernist façades that

have fallen out of fashion. A fundamental problem with the heritage system in Egypt is that it treats listed buildings as monuments not to be lived in or used, while the twentieth century produced only buildings that continue to be part of everyday life such as apartments, private houses, stores, and office buildings. A listed building in the current system must be fenced, removed from its context, or turned into a museum— something that contradicts the nature of many a heritage-worthy modern building that continues to serve its function.

Call for Reviews

If you would like to review the book for the Arab Studies Journal and Jadaliyya, please email info@jadaliyya.com

Hassan Fathy: An Architectural Life

Edited by Leila el-Wakil

About the Book

This fully illustrated volume represents the most comprehensive examination yet of the life and work of the great Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy (1900–89), and the regional and international significance of his contribution to the lived environment. Eleven Egyptian and international scholars reveal the man, his milieu, his goals and his passions, his concept of social living and his fight for a humane model for affordable housing in tune with the environment, the application of these concepts in his numerous plans and buildings, his relations with the establishment, the extent of his influence, and the lasting legacy of his completed projects. Generously illustrated with archival and color photographs and the architect’s own distinctive and beautifully decorated gouache plans and elevations, many never previously published.

Contributors: Leila el-Wakil, Camille Abele, Jo Abram, Rémi Baudou, Ahmad Hamid, Nadia Radwan, Samir Radwan, Ola Seif, Jessica Stevens-Campos, Mercedes Volait, Nicholas Warner.

About the Editor

Leila el-Wakil is professor of the history of architecture and architectural conservation at the University of Geneva.

In the Media

“[A] richly illustrated ode to Fathy’s life and career.”– AramcoWorld

Additional Information

14 April 2018

416 pp.

$95.00

ISBN 9789774167898

Where to Purchase

UK: Bloomsbury | Amazon UK

Excerpt

THE EARLY STEPS OF A “ROMANTIC” IN A LIBERAL EGYPT

By Mercedes Volait

The extraordinary international success of Architecture for the Poor (first published in French in 1970 and in English in 1973), in view of the very limited reception the book received in Egypt until well into the 1980s, caused Fathy to be considered for a long time as a unique personality, largely disconnected from the land where he was born—a “global” artist before his time. The man was most certainly different. In the eyes of the vast majority of his Egyptian colleagues he was without doubt a “romantic,” dedicated to an artistic pursuit of architecture, which already had little place in the prewar functioning of construction in Egypt, and would have even less in the course of the country’s demographic explosion. However, his work is also, in many respects, anchored in the so-called liberal years triggered by the end of the British Protectorate in 1922 and the commitment of the Egyptian elite to social progress, in particular for the rural classes. As concerns his architectural creations, the constructions from his youth participated fully in the aesthetics of the time, even if from the beginning his projects reveal a style that is wholly his own.

The First Drawings

It is not easy today to know how much the architect owed to his training at the Cairo Polytechnic School. His curriculum (1921–26) was established prior to the school reforms carried out by the Swiss teaching staff of the Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich, hired in July 1925 to renew the discarded syllabus. We know very little about the teaching staff who presided before then. They included an architect called W.J. Dilley, possibly British, of whom we know nothing. Mustafa Fahmi, a Francophile and supporter of the Beaux-Arts system, taught the theory of architecture there from 1923. Upon his return from Liverpool in 1924, the youthful Ali Labib Gabr provided teaching on the history of architecture. Fathy’s diploma project conformed entirely to the taste for orderliness and monumentality that was then propagated by the Liverpool School of Architecture, the institution responsible for the introduction into England of the Beaux-Arts pedagogical system and the emphasis onlarge-scale compositions intended to celebrate the Empire.4 Fathy’s subject was in all likelihood a court of law, with reference perhaps to the competition that took place two years earlier for the new headquarters of the Mixed Tribunals in Cairo, since the projects of student-architects at the Polytechnic School were often tied to the country’s most recent architectural trends. In 1934 fourth-year students worked on designs for a workers’ housing scheme in Abu Za‘bal, on the outskirts of Cairo, the theme of a competition organized that same year by the railway authority, which owned the land concerned, in order to relocate their workshops from the capital and offer affordable lodgings to their employees.

The rather dry treatment of the décor may well be attributable to Fathy, however, as may the balanced structure of the volumes. It is easy to be convinced of this when one observes another grandiloquent structure designed at the same time in Cairo (1925–27) by a graduate from Liverpool who entered the service of the Egyptian government after 1922: the architect Maurice Lyon. That flagship project by the architectural department of the Ministry of Public Works was destined to host the country’s very first telephone exchange; massive and imposing in scale, it exhibited both poor volumetric composition and an elaborate classicizing cornice, far removed from Fathy’s final diploma project.

His austere composition was repeated in his projects from the 1930s, wherein Fathy interpreted in his own manner the typologies inherent in Egyptian residential architecture of the early twentieth century. The house that he built for the Hosni family (1930) evokes the “apartment-villa” type, with large verandas crowned with balcony-terraces, of which hundreds of examples were being built in Cairo, notably at Heliopolis. These were composed of two, sometimes three, identical apartments built one above the other, with direct access from the street by a few steps to the first-floor apartment, and by staircase for those on the higher floors. This hybrid between the individual villa and the communal building allowed the extended family to preserve a common residential space, even if its organization differed from the traditional system in the strict sense.

The noticeable discontinuity in style between the ground and the upper levels of the Hosni villa suggests that the project involved adding stories to an existing single-storey structure, which was again a common practice in Egypt. The house designed by Fathy for the artist Hayat Muhammad (1938) is a variation on another recurrent theme of domestic architecture in the early decades of the twentieth century: the Italianate villa, or villine , with a tower at the angle housing the access to the upper floors and terraces. The house consisted of a volume spread out over two floors, lit by a large bay. The design is reminiscent of the work of the French architect Auguste Perret in Alexandria and Cairo, but also of equivalents in Heliopolis, in the Emile Kahil Villa (architect Raymond Antonious, 1934) or the unexecuted project for a house for Mrs. Annette Sékaly (architect Edouard Selim Zalloum, 1934). Whatever the exact nature of the program or the role of the clients in selecting the designs, these first projects were approached with a great economy of means. The same can be said of the massive Bosphore Casino, particularly successful in the composition of its façade. Its sober style is Fathy’s own; his Egyptian colleagues cultivated a more classical vein or a more decorative modernism.

Egyptian Modernism

It is a challenge to pinpoint Fathy’s place within Egyptian architectural modernity of the 1930s, given his multiplicity and the fact that his knowledge was still fragmentary and incomplete. In notes delivered in 1934 to The Builder, Arthur Fred Wickenden (1879–1956), who had recently started teaching architectural composition at the Cairo Polytechnic School, highlighted at the same time the extraordinary stylistic variety of residential constructions and their inconsistent quality, the best being capable of mixing with the worst or the mediocre in a single project, without restraint. Architects of all nationalities and cultures were then practicing in Egypt—French; Italian; British; and, more unexpectedly, some from central Europe (the Serb Milan Freudenreich and the Bulgarian Michel Radoslavoff, among others), as well as members of the Syrian–Lebanese and Armenian diasporas. The architect and critic Edmond Pauty went as far as to speak of “architectural chaos.”

Wickenden stressed the perverse effects of the low cost of ornament in fibrous plaster, “which gave unlimited scope to decorative plasterers with little or no training or taste.” In his opinion, it was this that had led in the 1920s to the flurry of over-ornamented Renaissance-style buildings, which aged badly due to the ubiquitous Egyptian dust that clung to their decorative reliefs. A number of observers attributed this practice of excessive ornamentation to the tastes of the local clientele. Wickenden nonetheless discerned the beginnings of a movement toward greater sobriety in the most recent constructions, and the decisive influence of the German school in the multiplication of long balconies and horizontal compositions, even though he considered verticality to be more appropriate to the climate and to the urban density. This aspect of early Egyptian modernity, before Sayed Karim made his master Otto Salvisberg famous through the journal al-Imara, is yet to be explored. We know that the Berlin architect Ernst Kopp as well as the Swiss Max Zollikofer were both active in Alexandria in the 1930s and may have brought the horizontal line with them, although as yet we know little about their work. The Swiss professors who held positions at the Cairo Polytechnic School after 1927 may also have acted as its mouthpieces; the class on civic construction and reinforced concrete was given until 1937 by a certain Geering. It is equally true that the German vein reflected the spirit of the time in the whole Mediterranean basin. It surfaced in part from the Italian production in Egypt, in the wake of the influence exerted by Erich Mendelsohn in Italy between the wars. The “Mannerist modernity” of the Alexandrian villas built by Mario Avena (1896–1968), and the rationalist projects of the young Italian architects who were Fathy’s contemporaries, such as Serafino di Jeva, Alberto Viterbo (one of Perret’s collaborators in Egypt), and Fernando Parvis, the proponent of the Movimento Italiano per l’Architettura Razionale (MIAR) in Egypt, produced several such realizations. Among the local followers of the concepts of horizontality and the continuous balcony were Antoine Selim Nahas (the French-trained designer of the Shusha Building, in about 1937, for example) and Muhammad Sharif Nu‘man (trained in Liverpool), who were both active as teachers. The former taught at the School of Fine Arts in Cairo, where he created the “Paris Prize” enabling the best students to pursue their studies in France, and the latter at the Polytechnic School where he was responsible for “Architectural Composition.”

Call for Reviews

If you would like to review the book for the Arab Studies Journal and Jadaliyya, please email info@jadaliyya.com

A Field Guide to the Street Names of Central Cairo

By Humphrey Davies and Lesley Lababidi

About the Book

The map of a city is a palimpsest of its history. In Cairo, people, places, events, and even dates have lent their names to streets, squares, and bridges, only for those names often to be replaced, and then replaced again, and even again, as the city and the country imagine and reimagine their past. The resident, wandering boulevards and cul-de-sacs, finds signs; the reader, perusing novels and histories, finds references. Who were ʿAbd el-Khaleq Sarwat Basha or Yusef el-Gindi that they should have streets named after them? Who was Nubar Basha and why did his street move from the north of the city to its center in 1933? Why do older maps show two squares called Bab el-Luq, while modern maps show none? Focusing on the part of the city created in the wake of Khedive Ismail’s command, given in 1867, to create a “Paris on the Nile” on the muddy lands between medieval Cairo and the river, A Field Guide to the Street Names of Cairo lists more than five hundred current and three hundred former appellations. Current street names are listed in alphabetical order, with an explanation of what each commemorates and when it was first recorded, followed by the same for its predecessors. An index allows the reader to trace streets whose names have disappeared or that have never achieved more than popular status. This is a book that will satisfy the curiosity of all, be they citizens, long-term residents, or visitors, who are fascinated by this most multi-layered of cities and wish to understand it better.

About the Authors

Humphrey Davies is the translator of a number of Arabic novels, including The Yacoubian Building by Alaa Al Aswany (AUC Press, 2004). He has twice been awarded the Saif Ghobash–Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation.

Lesley Lababidi is the author of Cairo Practical Guide (AUC Press, 2011, 17th ed.), Cairo’s Street Stories: Exploring the City’s Statues, Squares, Bridges, Gardens, and Sidewalk Cafés (AUC Press, 2008), and Cairo: The Family Guide (AUC Press, 4th ed., 2010). An active and well-traveled blogger, she currently lives between Cairo, Beirut, and Lagos.

In the Media

“This new guide to Cairo street names … is as sure to delight as to inform, being attractively written and full of arcane lore throughout.”—David Tresilian, Al Ahram Weekly

“[A]n amusing and informative journey through the tales behind Cairo’s street names.”—Egypt Today

“This guidebook is anything but ordinary . . . rekindles memories and brings to life the forgotten streets, lanes, alleys, and passageways of Central Cairo.”—Lisa Kaaki, Arab News

Additional Information

14 July 2018

252 pp.

$29.95

ISBN 9789774168567

Where to Purchase

UK: Bloomsbury | Amazon UK

Excerpt

Introduction

This is not a guidebook, or at least not one that will help the reader to get from A to B (let alone from A to Z). It sets out, rather, to help him or her to get from now to then or vice versa within those parts of the city that lie east of the Nile and west of medieval Cairo, from Midan Ramsis in the north to Midan Fumm el-Khalig in the south, as well as on the island of el-Gezira. In order to do so, it presents an alphabetical list of current street names, each with its former or alternative names, if any, in reverse chronological order, and provides, where possible, short descriptions of who or what each street is named for and the dates at which street names changed. An index at the end of the book links the former and alternative names to the current name of the street used in the main entries. The definite article el- and the letterʿ (ʿ ayn) are ignored in the alphabetization of entries.

It has been our aim to provide information for every officially recognized thoroughfare or public space, be it a shareʿ (street), hara (lane), ʿatfa (alley), darb (formerly, side street), sekka (connecting street), zuqaq (cul-de-sac), midan (square), or kubri (bridge), as well as a representative sample of passageways.1 The list contains 607 current street names and some 377 former and alternative names. Street names are transliterated (see below), and translated when they consist of more than a simple personal name, without title. Names that begin with a title are listed under that title but a cross-reference is provided, as titles are often dropped in casual references (for example, Shareʿ el-Shahid Zakariya Rezq is listed under el-Shahid with a cross-reference from Zakariya). Cross-references are also provided for foreign names (for example, Shareʿ Shambuliyon is cross-referenced from Champollion).

Before turning to the city as it is today, we should note three types of watery body, that though today absent or greatly changed, have exerted a ghostly influence over its development and are referred to in the text. These are the River Nile, the canals, and the lakes. The course of the Nile at the time of the Arab conquest of Egypt ran about a kilometer and a half to the east of its present bed, if the distance is measured at its greatest. From the mosque of ʿAmr ebn el-ʿAs, which was built on its bank, the river ran along today’s Shareʿ Sidi Hasan el-Anwar to west of Midan el-Sayyeda Zeinab, from there to Shareʿ Mustafa Kamel, from there to Shareʿ Muhammad Farid, from there to Shareʿ ʿEmad el-Din, and from there to Midan Ramsis; thereafter, it veered west to meet its present channel at Shubra. The river’s slow shift to the west—accelerating during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and only coming to an end with the engineering works of the nineteenth century—left behind a plain of alluvial soil (the luq of Bab el-Luq) dotted with swamps and ponds. This was originally given over, to the extent possible, to agriculture (hence the frequent occurrence of bustan, or ‘plantation,’ in street names). In addition, the occasional settlement grew up, either in the form of a hekr (an estate granted on a long lease to a member of the establishment, on which suburban communities often arose) or a manshiya (a housing compound for the elite); these have left their mark among the city’s street names. Other areas were turned into grounds dedicated to equestrian sports and military exercises.

At the start of the nineteenth century, the lands on which Cairo now stands were also traversed by two large canals. El-Khalig el-Masri (the Egyptian Canal), or el-Khalig el-Kebir (the Great Canal), whose origins go back to at least the Romans and probably to the pharaohs, was dug to provide a navigable channel between the Nile and the Red Sea. Much given to silting even in antiquity, it was re-dug by ʿAmr ebn el-ʿAs (c.585–664), Egypt’s first Muslim governor, at which point it became known as Khalig Amir el-Mu’menin (the Canal of the Commander of the Faithful). Neglected by the Umayads, it was dug again under the Fatimids, under whom it seems to have acquired its present name, though it was also sometimes referred to as el-Khalig el-Hakimi, after the Fatimid caliph el-Hakim be-Amrillah, or as Khalig Lu’lu’a, after a bridge over the canal named for a Fatimid governor, or, in a map produced by the French in 1800, as “Canal el-Soultany” (i.e., el-Khalig el-Sultani, or the Royal Canal). In Fatimid times, it defined the city’s western edge; by the mid-nineteenth century it traversed the center of the city, the quarters to its west having grown up under Mamluk rule. Before the river’s retreat to the west, its intake point had been located to the east of its present site, at a point some 300 meters west of today’s Midan el-Sayyeda Zeinab; it was extended from there to Midan Fumm el-Khalig (Mouth of the Canal Sq.) on the river in 1241. In its course toward the north, it followed that of the street that would replace it, originally known as Shareʿ el-Khalig el-Masri, now called Shareʿ Bur Said, and passed through the city walls at Bab el-Shaʿriya before continuing to the area of el-Daher, after which it crossed the desert to debouch into the lake system at the northern end of the Red Sea; by the nineteenth century, however, it no longer extended beyond el-Daher.

El-Khalig el-Naseri was dug by Mamluk ruler el-Malek el-Naser Muhammad ebn Qalawun in 1325. It provided water to el-Khalig el-Masri, at that time silted up along its initial stretch, as well as to el-Malek el-Naser’s new resort at Siryaqus, north of the city near Birket el-Huggag. It also formed a navigable route for commodities, irrigated lands exposed by the river’s westward retreat, and allowed the seasonal refilling of certain lakes (such as those of el-Azbakiya and el-Nasriya) that had become magnets for urban development. El-Khalig el-Naseri started at Qasr el-ʿEini, not far north of the intake of el-Khalig el-Masri, and ran more or less parallel to el-Khalig el-Masri a little less than a kilometer to its west, prefiguring and facilitating the building of today’s Shareʿ Qasr el-ʿEini, Shareʿ Talʿat Harb, and Shareʿ ʿUrabi, as well as the northern end of Shareʿ Ramsis. At a point about two hundred meters west of Midan Ramsis, it swung to the northeast to meet and merge with el-Khalig el-Masri just west of the mosque of el-Daher, about five kilometers from where it started. Stretches of the canal have been known by different names at different times. That most commonly used in what is now the Downtown area was Khalig el-Maghrabi, or el-Maghrabi’s Canal, after Sheikh Salah el-Din Yusef el-Maghrabi (d.1355), a Sufi saint whose tomb once stood close to its bank on today’s Shareʿ ʿAdli. A branch, Khalig el-Khor, survives in the form of a street name. Bridges over these canals, of which there were some twenty-four at the end of the nineteenth century, were called qanater, singular qantara. These survive today in street names such as Qantaret Qadadar and Qantaret el-Dekka.

Call for Reviews

If you would like to review the book for the Arab Studies Journal and Jadaliyya, please email info@jadaliyya.com