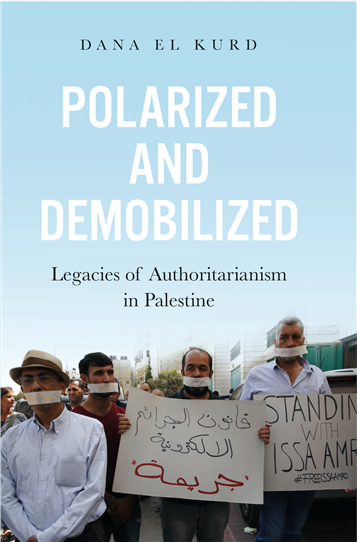

Dana El Kurd, Polarized and Demobilized: Legacies of Authoritarianism in Palestine (Hurst Publishers, October 2019).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Dana El Kurd (DEK): As a Palestinian, the conditions of stagnation and malaise that seemed to be increasing in Palestine were obviously at the forefront of my mind. So, I knew I wanted to research some aspect of that stagnation. I was most interested in why Palestinians were not able to mobilize like they had done in the past, and why their ability to face the occupation had weakened to such a degree.

I traveled to Palestine to start sketching out my project. There, while conducting an interview during preliminary fieldwork, one Palestinian Authority (PA) official interrupted the proceedings to insist that I “write how we got here.” I took that very seriously. I wanted to write a book outlining exactly the causal mechanisms linking international involvement to the PA’s authoritarianism, and how that externally-backed authoritarianism in turn affected and stunted Palestinian society.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

DEK: The book focuses on international-domestic linkages and authoritarianism, and then the impact of authoritarianism on society. The first part of the book looks at the former, and the second part the latter. For the first part, I did interviews with PA bureaucrats and decision-makers. I also conducted a nationally representative survey in the Palestinian territories to see how international involvement impacted public opinion differently from political elite opinion. I argued that political elites were divorced from their public precisely because of international intrusion into that relationship, and that was what made the PA more blatantly authoritarian overtime. The survey analysis and interview data confirmed this argument.

In the latter portion, the book addresses the impact of the PA’s indigenous authoritarianism on, specifically, polarization and protest. I analyzed how the PA’s repressive strategies had polarized Palestinian society, rendering society incapable of coordinating across partisan lines. I also used an original dataset (covering protests in the West Bank from 2007 to 2016) in conjunction with interviews conducted with activists to examine how this polarization impacted protests. I found that the PA’s selective repression strategies—targeting some groups while coopting others—was creating grievances between groups in Palestinian society, and insularity within them. This explains why we see rising levels of polarization and an inability to coordinate across party lines. Specifically, the most impacted groups were the Islamist parties, given the conditions of repression they have faced in the West Bank following the 2006 legislative elections. As for the protests, I found that they were most likely in non-PA areas, despite the ongoing repression of the Israeli occupation and, often, a lack of organizing institutions in those areas. This proves that the PA is having a specific impact on Palestinian society’s mobilization capacity.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

DEK: This is my first book, and it is my first project on Palestine. But, overall, it is connected to the themes of authoritarianism, repression, and mobilization, as well as international involvement in the Arab world, which my other projects (past and present) also focus on.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

DEK: I hope this book will be read by academics interested in authoritarianism in the Arab world, as well as academics specifically interested in Palestine. But, perhaps more importantly, I hope this book is read by those who work with or in Palestinian civil society. Ideally, I would want the takeaways of this book to help emerging Palestinian leaders pinpoint where things are going wrong, and also to help formulate alternative plans to mobilize Palestinian society once again.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

DEK: I am currently working on a second book project, concerned with the impact of Israel on authoritarianism in the Arab world. I hope to look at the diffusion of authoritarian technologies, as well as the impact of Israeli-Arab relations on state-society dynamics in normalizing states.

J: What is the impact of current American pressure (particularly Trump’s “Peace for Prosperity” proposal) on Palestinian leadership and society?

DEK: In my book, I have shown how an American and Israeli-backed PA—specifically following the 2006 legislative elections—has had a profound impact on Palestinian social cohesion. The PA was pressured to overturn democratic elections, crack down on legitimate dissent, and generally disrespect civil rights and the rule of law for the sake of Israel’s security. But, given the role of international funding, the PA has also been the strongest player in town; it has employed a large segment of Palestinian society and has had the capacity to get involved in grassroots organizations and their mobilization capacity. This has had the impact of crowding out other vehicles for organization.

Given that the Trump administration has just taken steps to cut funding to Palestinian security (in an attempt to strong-arm Palestinian leadership into cooperating with the peace proposal farce), this might lead to a scenario where the PA can no longer control and repress Palestinians to the degree they once did. This means Palestinians may have an opportunity to express their dissent to a larger degree than in the recent past, both against the occupation and against the Oslo paradigm.

Moreover, as I have written before on the subject, this moment represents an opportunity for the PA to finally restructure their relationship to society. Instead of being at odds with the will of the Palestinian people, now Trump has provided PA leadership with the excuse to realign themselves with the aspirations of everyday Palestinians. This would mean their complete rejection of the Trump proposal, the cessation of security coordination with Israel, as well the harnessing of Palestinian political will to mobilize against the current state of affairs. For a leadership without authority, presiding over a “state” without sovereignty, the biggest asset the PA has is the Palestinian people. They should therefore take the opportunity that Trump has presented, in the form of this plan, to finally represent their people, and to reject the Oslo paradigm which has left them stagnating since 1991. Given recent circumstances, this would seem quite reasonable to the international community, and Palestinian leadership can finally start finding a new path forward.

Excerpt from the book

Ayed is a political activist from a modest background. He grew up in a West Bank village under occupation, and did not have the opportunity to immigrate for work or higher education. He was in his late teens when the first intifada erupted. As a member of Fatah’s political arm, Ayed organized protests against the occupation. For his efforts, he was imprisoned in Ofer military prison with a 30 year sentence. But in the late 1990’s, Ayed’s luck turned around. As a part of a deal with the Israeli government, the Palestinian Authority – the new Palestinian government – was able to secure Ayed’s release.

Ayed returned to Palestinian society, but realized soon that much of the conditions of occupation remained exactly the same. He attempted a return to activism, and was involved for some time in organizing protests and sit-ins. He could not, however, find institutional support for his activism. There were few organizations in place to facilitate coordination, and Ayed felt like he was getting nowhere. The PA itself did not seem interested in getting involved in support of such actions, and encouraged him to take a bureaucratic position in their interior ministry instead. Facing economic hardship and unable to find alternative work, Ayed agreed. Today, Ayed talks of the past, and looks at his personal stagnation as symptomatic of the Palestinian struggle. “We come here and pretend to work,” he says, “but we are only pencil pushers.” He is unhappy with the PA’s policies, but can do little to challenge them, especially because he is dependent on them as a source of income.

This pattern of stagnation is not exclusive to Ayed; Palestinian society as a whole struggles with this general malaise. Prior to 1994, Palestinians were highly politicized and organized, despite a sustained loss of land and military occupation. Many Palestinians participated in a number of organizations throughout their daily lives – organizations that arose organically and functioned based on democratic practices. This not only had to do with the highly educated nature of Palestinian society, but also the reaction of Palestinian society to the effects of the occupation. Palestinians organized themselves in order to better provide services to their communities and coordinate effectively in their political objectives. Many of these organizations were highly responsive to their members, and the overall nature of Palestinian civil society was democratic and robust. Thus, when the first intifada erupted in the late 1980’s, dense civil society was one of the main reasons that Palestinians were able to sustain a diffuse, mostly non-violent uprising despite the heavy cost imposed on them by Israeli repression. The first intifada was locally organized and effective in its objectives, and sustained itself for four years. Although coordinated with the Palestinian Liberation Organization, a representative of the Palestinian people in the diaspora, local forces took the lead on organizing the uprising.

Following the intifada, the PLO entered into talks with the Israeli government and international powers including the United States and European nations. From these negotiations, the Palestinian National Authority emerged as a governing entity, intended to facilitate the transformation of the occupied Palestinian territories into a viable state within 5 years. Considering the context in which the PA was created – one which featured a highly organized population with robust civil society – it should have been the case that the PA would develop in a democratic and responsive manner, in accordance with the society they governed. Indeed, the development of democracy was a key stated objective according to the PA’s leadership and its international donors. As it turned out, however, the actual trajectory of the PA’s political development drastically departed from this objective.

Over time, the PA grew more authoritarian and began to erode the democratic underpinnings of Palestinian society. For example, scholars have noted the effect that the Palestinian Authority had on civil society organizations: civil society organizations became less effective, more isolated, and reported lower levels of trust amongst members. Throughout the 1990’s, the PA served to co-opt Palestinian institutions. Where cooptation did not work, the PA used repression. Palestinians began to recognize that the authoritarian nature of the new regime hindered their ability to mobilize.

For instance, when the five year deadline for statehood passed, Palestinians launched a second intifada. This uprising was very different from the first in terms of character and outcomes; it was much less organized, and achieved few of its political objectives. The disorganized nature of the second uprising also meant greater violence, as groups within Palestinian society found it harder to coordinate on common strategy and sanction spoilers. The authoritarian nature of the PA seemed to have wide-spread implications on how society functioned, and the political stagnation that has characterized Palestinian society since 1994.

International patrons were heavily involved throughout this process. The EU, Israel, and the United States were all engaged in setting the parameters of development and imposing pressure when the PA attempted to stray from their objectives. For instance, when the Islamist party Hamas won a plurality in the legislative elections of 2006, the US urged the outgoing party to launch a coup, and prevented the democratically elected members from taking power. The US in particular was also heavily involved in funding the PA’s security projects, and the EU provided technical support for the PA’s bureaucracy. When international patrons did not get their way, sanctions would follow and the PA’s funds would be withheld. In certain circumstances, Israel would intercede militarily and assassinate or imprison PA leadership. Over time, Palestinians have found themselves in gridlock, as the PA’s institutions cease to function as intended, and the grass-roots organizations that once mobilized Palestinians disappear from the scene.

How did the Palestinian Authority demobilize society, when years of Israeli occupation failed to do the same thing? I argue that the PA’s repression is more effective, and more damaging. The PA more successfully demobilized Palestinians because it is an indigenous authoritarian regime, rather than an external occupier. Despite Israel’s greater resources and international backing, the PA was able to utilize its ties within society and covert authoritarian strategies to accomplish what Israeli repression was unable to do: polarize and demobilize the Palestinian population.

Crucially, the PA developed in an authoritarian fashion in large part as a result of international involvement. International involvement, led by the US, encompassed a wide range of behavior including foreign aid and diplomatic pressure. This involvement created a disjuncture between the PA and Palestinian society. As a result, Palestinian leadership was insulated from their domestic constituency, consumed with addressing international pressures rather than negotiating with their own society. This insulation strengthened authoritarian practices. Not only did the role of international patrons becomes a polarizing issue amongst the public, but so did the practice of authoritarianism itself. My research demonstrates that certain authoritarian strategies used by the PA increased societal polarization. Rising polarization, in turn, affected a number of key outcomes, including patterns of mobilization and the capacity for collective action.

This dynamic is not unique to the Palestinian Authority. Across the Arab world, repressive regimes backed by international support have been able to polarize opposition forces and demobilize their societies. International involvement is a highly salient variable in the region. Where the interests of international patrons have been at odds with the interests of the domestic public, regimes deduce that accountability to their publics – or for certain segments of their publics – is no longer viable. Overall, international involvement that results in the insulation of the regime, thus facilitating the increased use of authoritarian practices, has profound societal impacts.