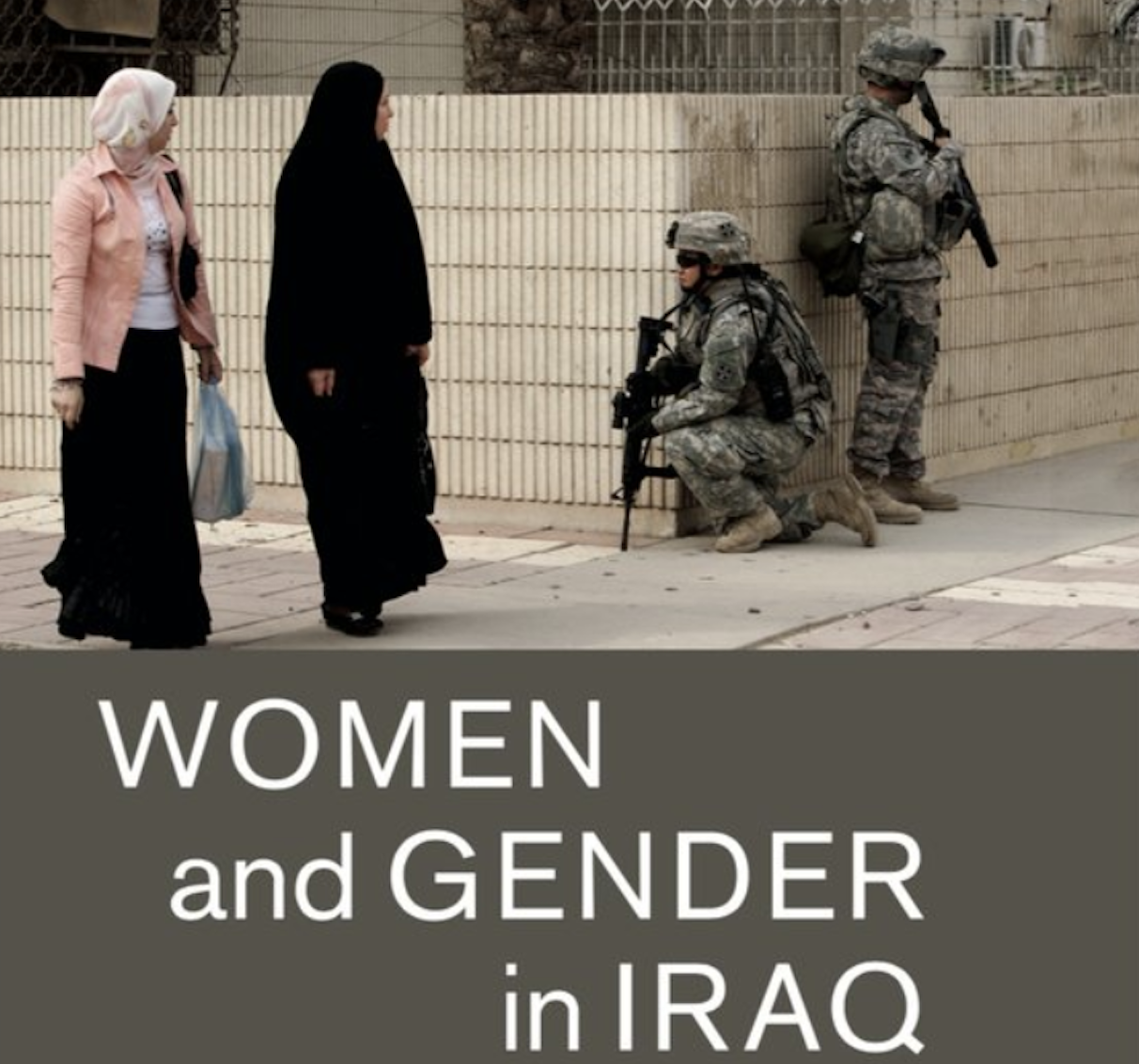

Zahra Ali, Women and Gender in Iraq: Between Nation-Building and Fragmentation, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Zahra Ali is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Rutgers University, New Jersey. Her research explores the dynamics of women and gender, social and political movements in relation to Islam(s), the Middle East, and contexts of war and conflict with a focus on contemporary Iraq.

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Zahra Ali (ZA): I wrote this book to shed light on the rich and unique social history of feminisms in Iraq as well as on Iraqi women’s original social, economic, intellectual, and political trajectories since the formation of the modern Iraqi state in the 1920s. I also wrote it to explain and analyze the mechanisms that led Iraq to be the hypermilitarized ethnosectarian fragmented country it is today and the centrality of women and gender issues in these processes.

I am a sociologist, a feminist, and a daughter of a family of Iraqi political exiles in France. I started with an observation regarding the realities of knowledge production regarding Iraq: First, the literature on the country has a predominant “white man political scientist” approach that focuses on political regimes and leaders, offering a limited and limiting analysis; recent research even makes it sound like everything started (or ended) in 2003. In contrast, my book offers a wider historical perspective beginning with the formation of the modern Iraqi state. Secondly, the scholarship of Iraqi diasporic intellectuals is often authored by the older generation and not always updated, especially in relation to the social dynamics existing inside the country. This is why conducting sociological research based on in-depth ethnographic fieldwork is so central in my book. I spent a lot of time throughout a period of two years inside the women’s movement, mainly in Baghdad but also in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah in Iraqi Kurdistan. More recently, I expanded my research to Najaf-Kufa, Karbala, and Nasriya. Thirdly, in terms of what is produced inside Iraq regarding its social, economic, and political history, relational/intersectional works and gender and feminist perspectives are clearly lacking. This book proposes a complex, nuanced, and multilayered understanding of Iraqi society with a strong historical perspective. I engage in an ethnographic approach with a very detailed research focus on Iraq’s social, economic, intellectual, and political histories.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

ZA: This book is a sociological study of Iraqi women’s social and political activism and feminisms through an in-depth ethnography of Iraqi women’s rights organizations and a detailed research on Iraqi women’s social, economic, and political experiences since the formation of the Iraqi state. Every single interview with female social and political activists (all between the age of twenty-one to seventy-four years old and from across the ethnic, religious, sectarian, and political spectrum) began with this question: Shenu eli khalash atkunin nashita neswiyya (what made you become a women’s right/feminist activist?). From the hours of conversation aroused by this question, I have gathered a transgenerational oral history of women’s social, economic, intellectual, and political lives since the 1950s. Through my participant observation with Iraqi women activists, we discussed and debated the current burning issues that mobilize women activists and the civil society in Iraq today, issues ranging from the Personal Status Code, ethnosectarian and political violence, as well as the militarization of the society. We also engaged in long conversations on the ways to define and experience social justice, gender equality, emancipation, and liberation.

My theoretical approach engages with transnational and postcolonial feminist literature, with a focus on the imbrication between issues of gender, nation, state, and religion. I look at the ways in which gender norms and practices, Iraqi feminist discourses, and activisms are shaped and developed through state politics, competing nationalisms, and religious, tribal, and sectarian dynamics, as well as wars and economic sanctions. I specifically look at the context following the US-led invasion and occupation and analyse the realities of Iraqi women’s lives, political activism, and feminisms, especially the challenges posed by sectarianism and militarism.

This book is as much about women, gender, and feminisms in Iraq as it is a feminist book about Iraq. As such, it seeks to contribute to critical feminist debates as well as to propose a feminist analysis of Iraq’s contemporary social, economic, and political history. It also enriches literature on gender(s), modern state(s), authoritarianism(s), nationalism(s), tribalism(s), religion(s), and social and political movements such as communism(s) and Islamism(s) in the Middle East as well as elsewhere in the world.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

ZA: I recently edited a journal volume entitled Decolonial Pluriversalism (in French Pluriversalisme Décolonial, co-authored with Professor Sonia Dayan-Herzbrun, Kimé, 2017) which explores decolonial theories reflecting on non-eurocentric epistemologies, aesthetics, political thoughts, and activisms. The volume draws on Latin American and Caribbean philosophies, concepts of creolization and racialization, and explores Afropean aesthetics, arts and cultural productions, religion, feminisms, fashion, education, and architecture.

Before that, I published another edited volume, Islamic Feminisms (in French Féminismes Islamiques, La Fabrique, 2012; translated and published in German, Passagen Verlag, 2014) that reflects on transnational Islamic/Muslim feminisms through a postcolonial and intersectional feminist perspective, analyzing the interrelationship between race, gender, religion, and postcoloniality. This book also drew on my ethnographic research within the anti-racist and Muslim feminists’ networks in France in which I was involved.

This book challenges some of my early theoretical perspectives, not only in adding complexity but more importantly in terms of contexts. Postcolonial and decolonial perspectives have emerged mostly in the field of literature and cultural studies, and as a result tend to focus on discursive dimensions rather than on the social and economic realities that structure them. Also, it is easy to be stuck in the West/Orient paradigm while trying to dismantle it. The book describes and analyses concrete forms of imperialism, colonial, and neocolonial domination, but more importantly, it offers a complex analysis of Iraqi women’s struggles for emancipation, equality, and justice. In this book, I am applying the “personal is political” feminist mantra not only in looking at what Iraqi social and political activists say or think but at the very concrete social, economic, and political contexts that shape their discourse and activism.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

ZA: My first audience is the Iraqi feminist activists with whom I spent time and from whom I learned so much throughout this research process. This book is for them and for the Iraqi civil, intellectual, and political society first and foremost. Its publication in Arabic is on its way. Then, I hope that feminist, anti-war, anti-imperialist, anti-racist, leftist, decolonial, and social justice activists and networks anywhere in the world will want to read this book. As I live in the US at the moment, I wish many Americans will read it, because Iraq, just like Vietnam, is present in the everyday life of this country, in its prison industrial complex, in its normalization of the military industry, in police violence, in anti-black and anti-immigration racism, and in its neocolonial white feminism and so many other aspects of its social, economic, and political life. In this sense, I wish many people in the UK will read it too as their governments have also been deeply involved in the invasion and occupation. I also wish it will be read by individuals and students studying the Arab region, the Middle East, feminisms, and gender.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

ZA: At the moment, I am working on two main projects, both focusing on the context following the Islamic State invasion of Iraq in 2014: the first is part of the project “Religion and the Framing of Gender Violence” supervised by Lila Abu-Lughod, Rema Hammami, Janet Jakobsen, and Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian at the Centre for the Study of Social Difference at Columbia University. It is a critical reflection on gender-based violence initiatives and campaigns in relation to the “War on Terror” narrative and politics inside Iraq. The second is part of the SSRC Conflict Research Programme based at the Middle East Centre at LSE; it is a sociological exploration of youth, grassroots and diverse forms of social and civil society activisms in Iraq. Through an in-depth analysis of the political economy of militarism and ethnosectarianism, I explore the articulation between different forms of structural violence, senses of belongings, and diverse discourses and concrete practices of political and social activisms.

Excerpt from the Book:

“Chapter 2. Women, Gender, Nation and the Ba ‘th Authoritarian Regime (1968-2003)”:

“The ‘Arif brothers’ takeover in November 1963 was merely a short breather before the second Ba‘th coup of July 1968. When the Ba‘th returned to power, campaign of repression and terror began again – including imprisonment, torture, intimidation, and executions – but this time targeting a broader political spectrum: communists, Nasserists, pro-Syrian Ba‘thists, old ministers and officials, alleged spies, and any other Ba‘th opposition. Nashwa A., born in 1943, remembers this period with great pain because her family -originally from Karbala- belongs to the renowned clerical class and includes several leading nationalist and communist figures. Two of her brothers were jailed in 1963 for being communist activists, and her brother-in-law, a young pilot and leftist activist, was executed. Nashwa’s brothers had fled to Germany, but one was caught by the regime’s security forces when he returned for a visit in 1968.

In 1968, after the coup, when my brother came back from Germany, they came and took him in front of his wife and son. I was the one who opened the door, and I confronted them. After that, I spent months running around between his prison and people that could help me get him out. I was terrified for him; I was young at the time. I was so active in trying to get him out that he even heard in prison “your sister is running around for you.” When he was finally released, he came back completely destroyed; he looked like nothing. He told us how he was tortured, savagely tortured; it was not possible to be tortured that way. They destroyed him. His teeth, they broke his teeth, he had cigarette burns all over his body, from his chest to his feet. He had scars from a whip on his feet that scarred his heels. Our [her brother’s name] was so sweet; he was the sweetest of the family. We could not bear to see him scarred like an animal. With time, he came back to himself. He became again the sweet and patient soul he was, and he is until today … He got treated after prison, because it was obvious that he had been tortured, but he had to hide it from people. After a while, he managed to escape to Germany with his wife and son, and I visited them there, although it was risky.

The Ba‘th regime, unlike its predecessor, stayed in power; hence the families of political prisoners and missing or executed activists endured harsh discrimination and control, which led some to flee the country when possible. In subsequent years, the Ba‘th brought the army and security services under its influence, and the Ba‘thification of Iraqi state institutions only furthered as Saddam Hussein’s power increased over Hasan al-Bakr, the head of state. With much of the power already secured, Saddam Hussein officially became president in 1979. Immediately after, Hussein embarked on a campaign of arrest and torture of political opponents and a violent purge of anyone suspected of opposing his clan’s, the Tikritis, hegemony within the party. In 1979, Maqbula B. -the previously quoted Iraqi Women’s League activist who was imprisoned and tortured in the infamous Qasr al-Nihaya prison after the 1963 Ba‘th coup- was again targeted. As she was away when the security forces came to her home, Maqbula’s elderly mother -a founding member of the Iraqi Women’s League- was arrested and tortured instead.

They came and took my mother. They took her because my car was registered under her name. They tortured her and interrogated her about me. They hit her and gave her 16 electric shocks on the most sensitive areas of her body: on her chest, and all the sensitive areas, despite the fact that she was over 60 years old!! [She cried] I wish she was here in order to tell you. They circled the house, waiting for me to come back. They were trying to get her to speak, [to] tell them where I was hiding. They continued to harass her until the fall of the regime. They even proposed to pay for her flight ticket to go and get me abroad.

Maqbula did not go home; she escaped, without a single personal item, the same day her mother was caught. After hiding inside the country for a year and having been reported as “missing” in Baghdad, she clandestinely entered Syria. Like many activists who fled during this period, Maqbula received support from Palestinian activists – from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – in the Damascus and Beirut refugee camps, and the Yemeni government provided her with a fake passport. Later her mother was able to secretly visit her in Syria. During Maqbula’s twenty-four years in exile, she lived in Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Russia, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria; throughout this time, she remained active in the opposition and the Iraqi Women’s League. In the mid-1980s, Maqbula even participated – along with the leading figure Hanaa Edwar – in the armed struggle of al-Ansar (the armed branch of the Communist Party in Iraqi Kurdistan) against the Ba‘th in the Kurdish mountains. After the fall of the regime in 2003, she was finally able to return to Iraq. Maqbula actively worked to rebuild the Iraqi Women’s League and she now participates in civil society activism in Baghdad.”

“Chapter 3. Experiencing the Invasion and Occupation and the Women of the New Regime”:

“Sectarian violence also impacts on women’s activists’ everyday lives. Among the activists I interviewed, most experienced the violence characterizing postinvasion Iraq directly through the death of a spouse, brother, sister, cousin, or neighbor. Explosives are the number one cause of women’s mortality in Iraq, as well as the leading cause of damage to the healthcare infrastructure. Both women and men adapt to make their way around Baghdad; the most common strategy is to avoid crossing sectarian boundaries, staying within one’s own neighborhood. In this context, a representative or public figure is exposed to violence in a peculiar way. Wafa F., for example, was married to a representative in the Fallujah Provincial Council. Her husband, a Shi‘a Islamist, was killed in front of Wafa and her three kids at the front door of their house by armed men emptying by force the area of Shi‘as. After the execution of her husband, Wafa was warned that she had to leave the city if she wanted to stay alive. She left with her kids and settled in a popular Shi‘a neighborhood of Baghdad. A housewife for almost a decade, Wafa had to turn over a new leaf and look for a job to provide for her family; she got involved in the Al-Fazila Party, a Shi‘a Islamist party, that offered her protection and support. Most of the women activists I interviewed, especially public and media figures, have received death threats or been directly targeted by violence – e.g., car bomb attacks in front of their offices or homes. Some had to flee the country or live in the Green Zone of Baghdad, but most remain in Baghdad.

Ibtihal I., age thirty-nine, a very active women’s rights activist of the Iraqi Women’s League narrated how, in an attempt to kill her, a group of men placed explosives in front of her house and made it explode in 2007. The event occurred after she had received several death threats from conservative sectarian militias in the form of phone calls and messages. Fortunately, no one was in the house at the time. Ibtihal speaks of the police incompetence and lack of will to help her find the perpetrators of the attack and provide her protection. She describes the atmosphere of Baghdad in 2006–7 and her feelings about it.

You know, in 2006 and 2007, after 2 pm, the streets of Baghdad were empty. There was no life in Baghdad. The next day, everything opened at 8 am. But people were scared to go out very early or later than 2 pm. Violence was everywhere. Armed groups, death threats, militias – the everyday reality was terrible, frightful. Until today, you know, the value of life is lost in Iraq. Any disagreement between political leaders ends up with violence in the streets. We face death every single day; every Iraqi who goes out of his house is not certain that he will come back alive. Iraq transformed into a scene of death. Even when we have moments of joy, we feel that we are stealing those moments, and we then refrain ourselves saying Allah yesterna [“May God protect us”]. The worse is that we do not even have a state, a government from whom we could seek protection or complain.”

[…] In addition to gendered sectarian violence committed by conservative sectarian militias, some women political activists have also been subject to violence for being part of the opposition to the new regime. Infiltration of hooded armed men and saboteurs in the demonstrations against the government is now a feature of the Iraqi political scene. More generally, an overwhelming sense of tension has been created by the violence, checkpoints, T-walls, fragmentation of Baghdad, and the dominance of competing armed militias in the streets. This feeling was expressed repeatedly to me: “Before we had one Saddam; today we have a Saddam at every street corner.” Many forms of human rights abuse and indiscriminate arrests and imprisonment of civil society activists by governmental elite related forces have been reported. During my interviews, I was told by many women’s rights activists that the repression of political mobilization against the new regime exposes women to a double sentence as torture and imprisonments are also synonymous with sexual violence. More generally, the case of both men and women victims of rape and different forms of torture in Iraqi prisons illustrates the failure of the new political regime to provide basic rights to its citizens. Violence and repression at the hands of government forces structures and challenges Iraqi civil society mobilizations in postinvasion Iraq.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]