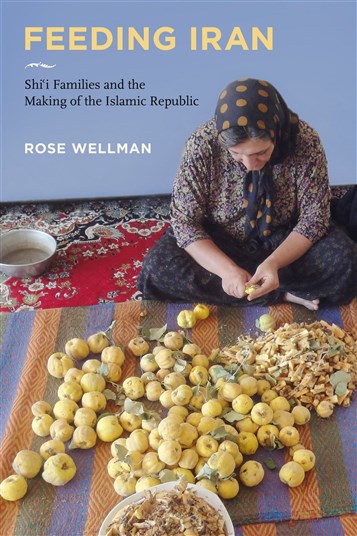

Rose Wellman, Feeding Iran: Shi`i Families and the Making of the Islamic Republic (University of California Press, 2021).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Rose Wellman (RW): Feeding Iran is an ethnography of religion and family life in the post-revolutionary Islamic Republic of Iran that focuses on Basiji families, members of Iran’s voluntary paramilitary organization. It is the first account of these state supporters outside of Iran’s urban centers since the 1979 revolution. My aim in writing Feeding Iran was twofold. First, I hoped to explore how home life and everyday piety are linked to state power. Too often we think about the family and the state as separate domains, whether of social life or scholarly inquiry. Feeding Iran, in contrast, shows the interplay between the intimacies of the home and the nation-state. It examines the multiple ways kin are discerned, protected, and shaped in Iran as well as the metaphorical and analogical resonances between the intimate spaces of the home and the nation. The book also explores how the more tangible substances and practices of kinship—such as blood, food, or family prayer—are being deployed in state rituals to create ideal citizens who embody familial piety, purity, and closeness to God.

Second, I wrote Feeding Iran to bring more nuance, humanity, and complexity to normative depictions and caricatures of Iran and its people, including of provincial state supporters. Ethnography, I contend, is a form of activism, and I see it as a necessary means of combating misinformation and Islamophobia. Forged through relationships and friendships on the ground, the work of doing and writing ethnography opens a window into the actual lives of everyday people, their family values, religious practices, and aspirations. Feeding Iran is the product of a year and a half of this kind of fieldwork, as well as of more than ten years of writing and research. It addresses the problematics of “writing Basiji lives” in light of popular media portrayals that depict the Basij as monolithic fundamentalists who stand in opposition to liberal modernity.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

RW: Feeding Iran is for anyone interested in the interstices of kinship, religion, and the nation-state. It draws heavily from new research on kinship and relatedness and reveals kin-making to be an embodied, sacred, and ethical process—as well as a social form that can provide emotional resonance, moral legitimacy, and literal substance to the nation. This is also a text for those interested in religion and Islam, particularly Shi‘i Islam. Feeding Iran explores how acts of piety and religious ideologies shape the family, and it addresses such topics as the meaning of the family of the Prophet in contemporary Iran, pilgrimage, votive meals, fasting, and the rites of Muharram. At the same time, the book is about food, and it endeavors to make a significant contribution to food studies. I show how food in Iran is more than a means of providing nutrition. Rather, it is an agent of transformation and a vehicle for channeling divine blessing, whether directed inward to the pure family core, which is materialized by the cloth upon which the family meal is spread (sofreh), or directed outward, for the spiritual nourishment of extended kin. But beyond the household, I explore how state elites and their supporters employ food to articulate, shape, and contest the making of an Islamic nation.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

RW: This is my first major academic research project, and as such, it largely grew out of my doctoral dissertation research at the University of Virginia where I earned a PhD in 2014. However, it departs from that earlier work by more deeply theorizing how the intimate practices of the home can link to state legitimacy and power.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

RW: I wrote this book for anyone interested in Iran, the Middle East, anthropology, ethnography, kinship, food, religion, and Islam. It is for undergraduate students, graduate students, and scholars. But the book is also for a wider audience—members of the public who hope to understand the hopes, dreams, and aspirations of provincial, state-supporting families in Iran. My aim is that this book helps provide a more nuanced, humanistic understanding of Iran, and of Basiji families, and that it helps clarify our understanding of the mutual resonances and naturalizing potential of kinship for state power.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

RW: In addition to continuing my research in Iran, as an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, I am currently conducting ethnographic fieldwork in Arab Detroit with Shi‘i Iraqi families. Shi‘i Iraqis of Detroit number in the tens of thousands and maintain more than fifteen active mosques and religious centers. I hope to explore how this community is striving to make a home in the Detroit area despite the ongoing impact of US foreign policy in the Middle East (and in Iraq), the US resettlement regime, anti-Muslim racism, and US state securitization efforts.

Excerpt from book (from the Introduction, pp. 1-3)

Nushin’s grasp is warm and firm. She pulls me through a crowd of women on the street, only a few feet from a similar group of men. I estimate that there are hundreds, if not thousands, of people gathered here on Fars-Abad’s main street in Fars Province, Iran. I use my free hand to clasp my black chador at my chin as I attempt to keep pace with Nushin’s steady progress. But the pressure of bodies increases as we near the slow- moving flatbed trailer pulled by a truck inscribed with the words “Yā Husayn.” I lose her hand in the crowd and call out. She nods briefly in apology but continues on. Nushin is now only a few feet away from the trailer containing two wooden caskets wrapped in Iranian flags. Inside the caskets lie the bodies of two unknown martyrs (shahid), fallen heroes from the Iran- Iraq War (1980–88). Their bodies have been brought here from the border of Iran and Iraq during the Week of the Sacred Defense, an annual commemoration of the war, and will be reburied in fresh graves in the town park.

Nushin has already, for just a second, managed to reach out and touch the wooden side of the trailer. Above and around her, other women throw the scarves that they have brought with them from home to uniformed male guards riding next to the martyrs. The guards in turn brush the scarves on the caskets, infusing the fabric with the blessing of the martyrs’ bodies and blood, before throwing them back. Behind us on the street’s median, Reza, Nushin’s teenage son, a budding computer scientist, is filming the proceedings with my camera. The footage he captures shows town officials, including the mayor, the droning of a military band, hundreds of townspeople, and a plethora of local media makers participating in the procession. The martyrs are on their way to their final resting ground, the town’s park.

The next Friday, the town’s prayer leader and local representative of state religion, the “Friday Imam,” holds a prayer and votive meal at the site of the new graves. I sit cross- legged on the ground next to Nushin and the other women while he introduces a “prayer giver,” who reads the Supplication of Kumail, a fifteen- minute prayer for the protection against the evil of enemies and for the forgiveness of sins. After the prayer, uniformed male soldiers distribute to the hundreds of men and women in attendance cups of yogurt, juice boxes, and plates of freshly cooked “lentils and rice” (adas polow) from giant metal vats located on the outskirts of the gathering. This food is paid for by the Foundation for the Preservation of Heritage and the Distribution of Sacred Defense, a parastatal group that had organized the multiday commemoration. As we eat the blessed fare, the Friday Imam speaks: “Because this martyr is unknown, we the people are his brother, his sister, his mother.” He calls on all of the attendees to think of themselves as the kin of martyrs, a kinship that is enacted in real time as the uniformed soldiers and townspeople call one another mother, father, brother, or sister in thanks as they receive and pass along food.

What aspirations compel Nushin and her fellow townspeople to reach out and touch the unknown martyrs’ caskets, attend their commemorative prayers, and eat blessed food at the site of their burial? What is the significance of this heartfelt participation in state ritual? And how does it relate to the everyday experience of living as kin in the Islamic Republic of Iran?

This book draws from a year and a half of ethnographic research among Shi‘i state–supporting families in the provincial town of Fars- Abad, the city of Shiraz, and Iran’s capital, Tehran, in order to understand how ideas and practices of kinship and religion are linked to state power. I ask: What can an analysis of home life and everyday piety tell us about contemporary nation- making? Answering this question requires an investigation into the metaphorical and analogical resonances between the intimate spaces of the home and the state. It also requires an on- the- ground exploration of how the substances and practices of kinship — from blood, to food, to family prayer — are being deployed in state rituals to create ideal citizens who embody familial piety, purity, and closeness to God. This book is for anyone interested in reimagining the interstices between kinship, religion, and the nation- state. It is about the hopes and dreams of ordinary Iranian supporters of the Islamic Republic. And it is the first account of these supporters outside of Iran’s urban centers since the 1979 Revolution.