Farid Hafez and Enes Bayraklı (eds.), European Islamophobia Report 2020 (Vienna, Leopold Weiss Institute, 2021).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you edit this book?

Farid Hafez and Enes Bayraklı (FH & EB): Farid had established the Islamophobia Studies Yearbook, originally in German and today bilingual, as the first academic journal dedicated to the study of Islamophobia back in 2010. While the academic world has become more conscious of this issue, many people in policy circles across Europe still underestimate the problem. That is why we came up with this idea in the first place. Both of us have been publishing this annual project since 2015. This is the sixth volume of the European Islamophobia Report. We started this project together with more than one hundred authors from all across Europe and covering more than thirty countries to provide data on Islamophobia in Europe to help anti-racist as well as Muslim organizations make more people aware of Islamophobia in their respective countries.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

FH & EB: The report has the character of a policy paper, showing how Islamophobia manifests in different fields, from the labor market to media, politics, the justice system, hate crime, and the internet. By providing this structure, one can easily compare the situation in across different European nation states, as well as within one country, over the course of many years. In addition, every single country report concludes with recommendations for policy makers and civil society actors to tackle general as well as very specific problems that pose a challenge in those countries. While other institutions such as the European Union’s Fundamental Rights Agency or the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe have produced reports that provide huge quantitative data, we are interested in identifying important moments and developments within a year that define the state and development of Islamophobia.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

FH & EB: There are several aspects unique to this project. First, it was intended as an annual report. Second, it was the first report to cover not only the West of Europe, but also many countries in the East. Before 2015, most of the academic literature discussing Islamophobia had focused on Western Europe. But we have also included countries with a sizeable native Muslim population, such as Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Albania, as well as countries such as Estonia, Lithuania and Poland, where Muslims represent very small minorities; we have thus been able to broaden the discussion on Islamophobia in Europe.

The European Islamophobia Report is more a policy oriented work, while most of Farid’s previous work has been academic and dedicated to the study of very specific questions such as Islamophobia in parliamentary debates, Muslim civil society activism, antisemitism and Islamophobia, and the institutionalization of Islam in Europe. Enes in the past has been engaged in think tank work a lot, covering a wide range of topics from German politics to Turkey’s foreign policy.

Together, we also published a book in 2019 dedicated to research on Islamophobia in Muslim majority societies, which was important for us since we wanted to show how Islamophobia is not a phenomenon geographically limited to the Western world, but rather—as many decolonial scholars have argued—a manifestation of the expansion of a racial global hierarchy that is deeply rooted in colonial structures of oppression.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

FH & EB: We produced this report on one hand to help the marginalized Muslim communities in Europe and on the other hand to support all the anti-racist forces in Europe, as well as well-intended people in bureaucracy and politics, who want to change the world for the better. We believe that we have already achieved something in this regard, having observed conferences and governmental as well as non-governmental reports drawing on our expertise.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

FH & EB: Farid Hafez is currently working on a book with Naved Bakali with the title “Global Islamophobia in the War on Terror: On Coloniality, Race, and Islam.” Enes Bayraklı is currently working on the first comprehensive anthology on Islamophobia in Turkey.

J: How do you define Islamophobia in your report?

FH & EB: In our report, we have suggested the following working definition of Islamophobia: “Islamophobia is about a dominant group of people aiming at seizing, stabilizing and widening their power by means of defining a scapegoat – real or invented – and excluding this scapegoat from the resources/rights/definition of a constructed ‘we’. Islamophobia operates by constructing a static ‘Muslim’ identity, which is attributed in negative terms and generalized for all Muslims. At the same time, Islamophobic images are fluid and vary in different contexts, because Islamophobia tells us more about the Islamophobe than it tells us about the Muslims/Islam.” What is important is that we see Islamophobia not only as manifested on an interpersonal relationship, but also on a structural level. At the same time, we are aware that there are many different approaches to the study of Islamophobia.

Excerpt from the book (from Chapter 1, pp. 9, 21-23)

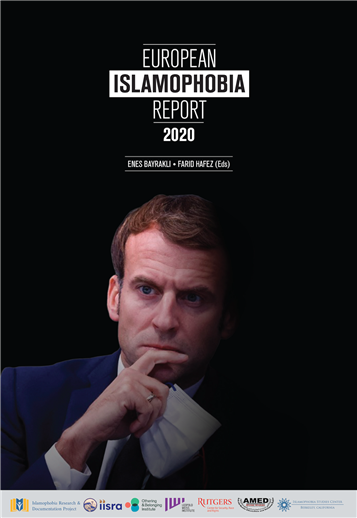

The year 2020 was an eventful year for Islamophobic developments, even setting the global spread of COVID-19 aside. The cover of this year’s report shows French President Emmanuel Macron, who have severely cracked down on Muslim civil society and anti-racist activists and scholars in France. With the “Law Confirming the Principles of the Republic” (originally entitled “Law against Separatism”), the Macron government further institutionalized Islamophobia and adopted an authoritarian style. France witnessed an increasing number of police searches, threats of eviction, as well as mosques and school closures, including the dissolution of a humanitarian NGO and a human rights organization defending Muslims in France against racism and discrimination. All together these threatened the fundamental freedoms of Muslims, in specific, and more broadly reveal a shift towards a restriction of citizens’ rights and freedoms. France has arrived at a state where the French interior minister Gérald Darmanin even singled out the long-time Islamophobic far-right party leader Marine Le Pen for “being too soft on Islam.” Similarly, in Austria a raid against pro- ponents of alleged “political Islam” was made one week after the murderous attack on November in Vienna. The home of several civil society activists were also raided and their bank accounts and assets were frozen on the suspicion of being terrorists that want to topple the Egyptian regime, destroy Israel, and create a worldwide caliphate. The raid was based on a report written by Lorenzo Vidino that argues that Islamophobia is a combat term used by political Islamists “to foster a siege mentality within local Muslim communities, arguing that the government and Western societies are hostile to them and Islam in general.” Hafez had already criticized this report as a method used in a systematic way to “produce knowledge to define vocal and representative actors of the Muslim civil society as potentially radical and Islamist, which then should lead to state and civil society exclusion.” (…)

Politics

Islamophobia has become quite mainstream in the political discourse of many European countries. As several studies reveal, especially the racist discourse of the far right, even if in opposition, has an impact on the overall debate about Islam and Muslims, and continuously extends the boundaries of reasonable and acceptable speech. Far-right politicians, such as the member of the Swiss SVP Andreas Glarner, claim to mobilize against an alleged “preference for Islam.” When the far right is in power, Islamophobia becomes legalized. In Staffanstorp and Skurup, two municipalities of Sweden, where the far-right Sweden Democrats are governing, the hijab was banned. When a school principal resisted, he received death threats by anti-Muslim and racist groups.

Still, it is not only the obvious and blatant Islamophobic speech by far-right politicians like the Austrian FPÖ chairman Norbert Hofer, who said during a party convention “Corona is not dangerous. The Koran is much more dangerous,”that exacerbates the public discourse on Islam and Muslims. It is also the – nominally speaking – mainstream politicians that have fully embraced an anti-Muslim agenda, al- though in a much more subtle way. Following a police raid on November 9, 2020 that targeted Muslim civil society and not alleged “terrorists,” Chancellor Sebastian Kurz stated, “We have to fight two challengers: First, the corona pandemic and second to fight even stronger against terrorism and radicalization in Austria and Europe.” Similarly, other governing parties that do not belong to the far-right political camp, are supporting an anti-Muslim discourse. An MP from the governing Nea Dimocratia (New Democracy) in Greece spoke about the niqab as “violating women’s rights,” raising the question of regulating it by the state. Following a discussion on migration in Brussels with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán stated publicly, “We don’t think a mixture of Muslim and Christian society could be a peaceful one and could provide security and a good life for people.” Finnish Minister of the Interior (Greens) Maria Ohisalo pointed out, “Freedom of speech also comes with responsibility. Speech about immigration turns into hate speech when it is directed at individuals or certain groups in a derogatory way.” This is what we are witnessing on a wide scale by several politicians in power.

Following Brexit, the European Parliament currently counts 705 members. While the far-right political group Identity and Democracy (formerly Europe of Nations and Freedom) did not become the fifth-strongest party group in the elections for the European Parliament in 2019, after Brexit, it became the fourth-strongest party, passing the Greens.With 76 seats, Identity and Democracy represents the most successful political group whose members share an anti-Muslim agenda.

Note: The report can be read online for free here.